Today I wanted to look at a question which is rarely asked: Why did the Catholic Church reject Luther’s doctrine of “faith alone”? Was it because they were pure evil? Or was there was actually something wrong with Luther’s philosophy?

That’s what I want to explore today.

Myths and Legends:

The tale is often told in popular culture of Martin Luther bravely taking on a hopelessly corrupt Church. One which forced its captive people onto a treadmill of good works – trying to earn their salvation.

Luther (as the story goes) managed to find a copy of the Bible in a dusty basement, read it for himself, and discovered that salvation is a free gift given of God’s grace. Rome roared in horror at this doctrine, and excommunicated Luther and all who followed him.

That’s the legend anyway.

Because of this, one experience familiar to many Catholics is for their other Christian friends to assure them:

“Our good works are a fruit of justification - not a cause of it. We can’t work our way into Heaven! You can’t earn God’s love and mercy. It is a gift of God’s grace!”Now, it is to their great credit that many Christians want to share the Gospel with their Catholic friends. However, what they don’t realize…. is that the Church absolutely agrees with them. The Catechism of the Catholic Church says:

"Justification has been merited for us by the Passion of Christ who offered himself on the cross as a living victim, holy and pleasing to God, and whose blood has become the instrument of atonement for the sins of all men." - CCC 1992

"Our justification comes from the grace of God. Grace is favor, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life." - CCC 1996

"With regard to God, there is no strict right to any merit on the part of man. Between God and us there is an immeasurable inequality, for we have received everything from him, our Creator." - CCC 2007

In other words, the thing which most people assume is the core issue… has never been an issue at all.

So what was is the problem?

Law, Gospel, and Faith Alone:

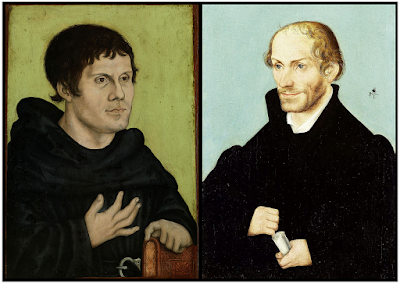

To explain this, I’m going to make frequent references to a work named “The Apologia for the Ausberg Confessions”. This was a long treatise written by Martin Luther’s friend and expositor Philip Melanchthon, which goes to great lengths defending Luther’s theology against the damnable “Adversaries” (Catholics).

Melanchthon begins his article on justification by explaining the overall pattern which Luther brought to Biblical interpretation. He said:

"All Scripture ought to be distributed into these two principal topics, the Law and the promises. For in some places it presents the Law, and in others the promise concerning Christ." - Apologia for Ausberg, Article on Justification, 5This is known in Lutheran circles as the Law / Gospel distinction. The mark of a good theologian – in their eyes - is the ability to note the difference between the two as they are found in Scripture. And one must never, ever confuse one for the other because of their exclusively distinct roles in the Christian life.

Law:

The "Law" consists of all the moral demands of God. The Law shows us how screwed we’d be if we went to our judgment. Thus, it shows us our need for a savior.

Now, the Law is said to have several roles in the Christian life, but the only way it is involved in our salvation is in terrifying us and driving us toward faith in the Gospel. Melanchthon puts it this way:

"In true griefs and terrors this sentence is perceived. Therefore the handwriting which condemns us is contrition itself. [...] But faith is the new sentence, which reverses the former sentence, and gives peace and life to the heart." - Apologia for Ausberg Confessions, On Repentance, 48

Gospel:

The Gospel is the promise of Christ to forgive the sins of any who approach him by faith. “Faith” – in this instance – has a very particular meaning. Melanchthon defined “justifying faith” in this way:

"But that faith which justifies is [..] to assent to the promise of God, in which, for Christ's sake, the remission of sins and justification are freely offered. It is the certainty or the certain trust in the heart, when, with my whole heart, I regard the promises of God as certain and true, through which there are offered me, without my merit, the forgiveness of sins, grace, and all salvation, through Christ the Mediator." - Apologia for Ausberg Confessions, Article on Justification, 48In other words -(and this is important)- "Justifying Faith" equals:

"Belief and trust in promises of Christ for the unmerited forgiveness of sins".

Putting it Together:

So the overall picture in Luther’s system goes like this:

- A person hears the Law of God.

- That person is terrified by the prospect of condemnation.

- The person hears the promises of Christ.

- He believes in trusts in those promises.

- Based on that belief and trust alone, his sins are forgiven and he is declared righteous by God.

- The Holy Spirit begins turning the person away from his wicked ways.

Now you might be asking, “What the heck could be wrong with that?”

The Antinomian Problem:

There is a certain type of error a Christian can fall into called “Antinomianism”. That word refers to a person who uses the graciousness of God’s forgiveness as an excuse to keep on sinning - and sinning gravely.

In other words, the person follows the above steps from 1 to 5 - he hears the Law and flees to the Gospel. But upon reaching the Gospel he dismisses the Law like a taxi. Now that he believes in the promises of the Gospel, he is confident in his salvation and sees no reason to depart his wicked ways.

Let’s put this in a concrete situation:

A Christian woman is married and has kids. She meets some guy at her office and develops a relationship with him. Eventually, this grows into a full-on adulterous relationship.Here’s the question:

Now, she knows adultery is a sin – and a particularly bad one. However, she decides to continue on with the relationship for two reasons. 1) It makes her happy, and 2) she knows Jesus will forgive her sins. In other words, she trusts Jesus SO MUCH… that she sees no reason to stop committing adultery.

Is this unrepentant adulteress, who trusts in Jesus, still justified before God?

Well, recall that Luther’s philosophy defined Justifying Faith – (which, again, is the one and only thing involved in salvation) – as belief and trust in the promises of Christ. Does she still have that? Yes, yes she does.

So is she still saved? If we are to be consistent with Luther’s theology… the answer is yes. She can commit adultery all day long and still be saved as long as she believes in Christ’s promises. In fact, Luther himself said the following in a letter he wrote to Melanchthon:

“Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. [] It suffices that through God's glory we have recognized the Lamb who takes away the sin of the world. No sin can separate us from Him, even if we were to kill or commit adultery thousands of times each day. Do you think such an exalted Lamb paid merely a small price with a meager sacrifice for our sins? Pray hard for you are quite a sinner.” – Luther’s Letter to Melanchthon on the Feast of Saint Peter, 1521Compare that to what Saint Paul said when writing to the misbehaving Christians at Corinth:

“You inflict injustice and cheat, and this to brethren! Do you not know that the unjust will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived; neither fornicators, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor prostitutes, nor practicing homosexuals, nor thieves, nor the greedy, nor drunkards, nor slanderers, nor swindlers will inherit the kingdom of God.” – 1 Corinthians 6:8-10Are you starting to see an issue here?

Melanchthon’s Reponse:

Now, I’m not the first person to point this out. You can actually see in the Apologia that Melanchthon had received the same critique. He responded to it in two places. Here’s how:

"But since we speak of such faith as is not an idle thought, but of that which liberates from death and produces a new life in hearts, (which is such a new light, life, and force in the heart as to renew our heart, mind, and spirit, makes new men of us and new creatures), and is the work of the Holy Ghost; this does not coexist with mortal sin (for how can light and darkness coexist?), but as long as it is present, produces good fruits, as we will say after a while." - Apologia on Justification, 64

"They say that these passages of Scripture (which speak of faith), ought to be received as referring to a ‘fides formata’, i.e., they do not ascribe justification to faith except on account of love. Yea, they do not, in any way, ascribe justification to faith, but only to love, because they dream that faith can coexist with mortal sin." - Apologia on Justification, 109

Were you following that?

First he notes that conversion is a gift of the Holy Spirit (which it is). Then he concludes the conversion of one's moral life proceeds necessarily from having faith. In other words, the Holy Spirit will unfailingly assure that a person who trusts Jesus will leave behind his/her sins.

Thus, in regard to a person who trusts in Jesus and yet decides to persist in sin, Melanchthon claims the Holy Ghost would never allow such a thing. He goes as far as to call it a “dream”.

Except it’s not a dream! I’ve seen a fair amount of it in my own life. Most Christians have. Heck, Paul's first letter to the Corinthians was written to a Christian community which was getting drunk at Mass, suing each other, forming factions, and visiting prostitutes... all while repeating the slogan, "All things are lawful for me." [1 Corinthians 6:12]

So no, it is far from being a dream. It has been a constant temptation throughout Christian history.

A Second Attempt:

Perhaps as a result of this weakness, Lutheran theology suffered some early fights with Antinomianism. These battles reached a conclusion when a council of Lutheran theologians published a work called “The Epitome of the Formula of Concord”. This work explicitly condemned Antinomianism… but did so in a peculiar way.

The “Epitome” began by reiterating that “justifying faith” would be defined as belief and trust in the promise of Jesus for the forgiveness of sins. And that it is on this basis alone that a person is justified and saved. It said:

“We believe, teach, and confess that this faith is not a bare knowledge of the history of Christ, but such a gift of God by which we come to the right knowledge of Christ as our Redeemer in the Word of the Gospel, and trust in Him that for the sake of His obedience alone we have, by grace, the forgiveness of sins, are regarded as holy and righteous before God the Father, and eternally saved.” - Epitome of the Formula of Concord, III-6Then it condemned Antinomianism by saying:

“We also reject and condemn the dogma that faith and the indwelling of the Holy Ghost are not lost by willful sin, but that the saints and elect retain the Holy Ghost even though they fall into adultery and other sins and persist therein.” - Epitome of the Formula of Concord, IV-19In this instance they assert that the Antinomian has actually lost his faith. This means they are saying the Antinomian actually doesn’t believe in the promises of Jesus anymore.

But that’s precisely the problem!

The Antinomian has not lost his trust in Jesus for the forgiveness of sins. That’s one thing he hasn’t lost. He is using that sincere trust and belief as an excuse to continue on in mortal sin. So in their second attempt they still were not able to deal honestly with the problem.

That’s the real reason why the Church had to reject Luther’s thoughts.

Epilogue: What’s Love Got to do With it?

One last thing. What is the true answer to the Antinomian Problem? You can see a preview of it when Melanchthon referred, with great disdain, to “fides formata”. The term is Latin for “formed faith”.

There is a true way of referring to “faith” which only refers to belief in promises. But Melanchthon’s critics were trying to explain that this is conception is too one-dimensional to capture the whole essence of “justifying faith” – (or as others may call it, a “living faith”).

It is a gift which entails more than simply believing in promises. Justifying faith also includes a disposition toward loving and obeying God. We see glimpses of this multifaceted concept when Saint Paul refers to things like the "obedience of faith" [Romans 1:6] and “faith working through love” [Galatians 5:6].

The problem with the Antinomian is that he’s accepted the part of "living faith" about believing in God’s promises, but he has rejected those parts which pertain to the love of God. And as Saint Paul said to the Corinthians:

"If I have all faith so as to move mountains but do not have love, I am nothing." - 1 Corinthians 13:2What Luther and Melanchthon failed to see was that the clear cut divide between Law and Gospel breaks down when we consider Love. Yes, it is something which God demands from us. But it is also the gift God gives us for our salvation.

In your other piece on justification, you said that the Catholic church alone looks at particular teachings holistically, considering all that the Scriptures have to say on that subject (even though you completely ignore St. Paul's teaching on imputed righteousness in Romans 4). But here, you're doing what you accuse non-Catholics of doing with the Scriptures--cherry-picking out of context things Luther (and Melancthon) wrote, not considering the context they were written in. Therefore, as an apologist, you certainly are making it harder for the non-Catholic to believe the other things you write about when here you're so obviously taking the writings of these Reformers out of context.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading. Let me know if there is anything in the context of those statements which you think scuttles the thesis I've put forward.

Delete